Coronary Artery Fistula

A coronary artery fistula is an abnormal communication between an epicardial coronary artery and a cardiac chamber, major vessel (vena cava, pulmonary veins, pulmonary artery), or other vascular structure (mediastinal vessels, coronary sinus) (see: cavf-1a, cavf-1b, cavf-2, cavf-3, cavf-4a, cavf-4b and cavf 5). In other words, some of the oxygenated blood from the lungs, which has come into the left ventricle and is pumped out into the ascending aorta to feed the coronary arteries and the rest of the body, is being siphoned off by the fistula into the right ventricle, atrium or other vascular structure.

This infrequent abnormality can affect persons of any age and is the most important hemodynamically significant coronary artery anomaly. Many are small and found incidentally during coronary arteriography, whereas others are identified as the cause of a continuous murmur, myocardial ischemia and angina, acute myocardial infarction, sudden death, coronary steal, congestive heart failure, endocarditis, stroke, arrhythmias, coronary aneurysm formation (rupture, emboli), or superior vena cava syndrome. Some of the symptoms or complications are related to the amount of blood loss into the shunt and how much stress is placed on the left ventricle to compensate.

Of over 33,000 patients undergoing coronary arteriography, coronary artery fistula occurred in 0.1 percent, whether due to congenital or acquired causes (Table see below ). Fistulas from the right coronary artery are more common than from the left, and over 90 percent of the fistulas drain into the venous circulation. Most fistulas are single communications, but multiple fistulas have been identified.

The natural history of coronary artery fistulas is variable, with long periods of stability in some and sudden onset or gradual progression of symptoms in others. Spontaneous closure is uncommon.

Surgical repair of the fistula is recommended for symptomatic patients and for those asymptomatic patients at risk for future complications (coronary steals, aneurysms, large shunts). Transcatheter embolization of fistulas has been reported. Direct connection between a major epicardial coronary artery and a cardiac chamber or major vessel (vena cava,coronary sinus, pulmonary artery) is the most hemodynamically significant coronary artery anomaly(see figures above) Myocardial ischemia has been documented in some patients with coronary artery fistulas, who have no evidence of atherosclerosis.

A 25-year-old asymptomatic marathon runner was found during a routine examination to have a continuous murmur that was more pronounced during systole and loudest at the aortic root on the right side of the sternum. Coronary angiography revealed a fistula connecting the left main coronary artery with the right atrium. Since we could not rule out the possibility that this abnormality could result in sudden death during overexertion, the patient was advised to reduce his level of physical activity. In about 55 percent of cases of coronary arteriovenous fistula, the right coronary artery or its branches are the site of the fistula; the left coronary artery is involved in about 35 percent of cases, and both coronary arteries are involved in about 5 percent of cases. The connection between the left main coronary artery (LCA) and the right atrium (RA) is unusual. Drainage occurs into the right ventricle in 41 percent of cases, the right atrium in 26 percent, the pulmonary artery in 17 percent, the left ventricle in 3 percent, and the superior vena cava in 1 percent; in the other 12 percent of cases, there are multiple connections between the fistula and different chambers of the heart. About half the patients with large fistulas are asymptomatic, whereas in the other half, congestive heart failure, infective endocarditis, or myocardial ischemia develops or the fistula ruptures. Pulmonary hypertension may occur when the fistula drains into the pulmonary artery. Survival into adulthood is the rule in these patients, but life expectancy is reduced.

HELMUT BRUSSEE, M.D.and ROBERT GASSER, M.D., PH.D NewEJM, Vol.346, No.12, P904, 3/21/02

Causes and Associations of Coronary Artery Fistula

I. Congenital

1. Embryonic

2. Multiple; systemic hemangioma

II. Acquired

1. Closed-chest ablation of accessory pathway

2. Percutaneous coronary balloon angioplasty8789

3. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy

4. Right/left ventricular septal myectomy'°'

5. Penetrating and nonpenetrating trauma

6. Acute myocardial infarction

7. Dilated cardiomyopathy

8. Mitral valve surgery

9. "Sign" of mural thrombus

10. Tumor

11. Permanent pacemaker placement

12. Cardiac transplant

13. Endomyocardial biopsy

14. Coronary artery bypass grafting

Pathophysiology:

The pathophysiologic mechanism of CAF is myocardial stealing or reduction in myocardial blood flow distal to the site of the CAF connection. The mechanism is related to the diastolic pressure gradient and runoff from the coronary vasculature to a low-pressure receiving cavity. If the fistula is large, the intracoronary diastolic perfusion pressure diminishes progressively.

The coronary vessel attempts to compensate by progressive enlargement of the ostia and feeding artery. Eventually, myocardium beyond the site of the fistula's origin is at risk for ischemia, which is most frequently evident in association with increased myocardial oxygen demand during exercise or activity. With time, the coronary artery leading to the fistulous tract dilates progressively, which, in turn, may progress to frank aneurysm formation, intimal ulceration, medial degeneration, intimal rupture, atherosclerotic deposition, calcification, side-branch obstruction, mural thrombosis, and, rarely, rupture.

Anatomy

Normally, 2 coronary arteries arise from the root of the aorta and taper progressively as they branch to supply the cardiac parenchyma. A fistula exists if a substantive communication arises that bypasses the myocardial capillary phase and communicates with a low-pressure cardiac cavity (atria or ventricle) or a branch of the systemic or pulmonary systems.

Normal thin-walled vessels exist at the arteriolar level that may drain into the cardiac cavity (arteriosinusoidal vessels) and venous communications (thebesian veins) to the right atrium. These small vessels do not steal significant nutrient flow and do not constitute fistulous connections. Fistulae usually are large (>250 mm) and dilated or ectatic, and they tend to enlarge over time. Often, the limits of what constitutes a fistula and what constitutes a normal vessel are debated.

Most fistulae arise from the right coronary artery (60%) and terminate in the right side of the heart (90%). The most frequent sites of termination, in descending order, are the right ventricle, right atrium, coronary sinus, and pulmonary vasculature. Coronary fistula communications often appear in the context of other congenital cardiac anomalies, most frequently in critical pulmonary stenosis or atresia with an intact interventricular septum, but also in pulmonary artery branch stenosis, coarctation of the aorta, and aortic atresia. Although most often congenital, a coronary fistula rarely may arise as a consequence of surgical resection of obstructing right ventricular muscle bundles (as in tetralogy of Fallot), endomyocardial biopsy, or penetrating or blunt trauma.

Embryology

CAF may appear as a persistence of sinusoidal connections between the lumens of the primitive tubular heart that supply myocardial blood flow in the early embryologic period. These channels most often persist when associated with outflow obstruction (eg, pulmonary atresia), yet they also may persist in the absence of obstruction.

Associated syndromes include pulmonary atresia or stenosis with an intact ventricular septum. In this setting, epicardial coronary blood may flow to and fro during the cardiac cycle. In systole, right ventricular flow decompresses via coronary-sinusoidal connections to the aorta in a reverse direction, while in diastole, the aorta perfuses the coronary artery in a normal antegrade fashion. This contrasts with coronary arteriovenous fistulae in the absence of outflow obstruction, in which coronary steal is the primary pathophysiologic problem. In pulmonary atresia and coronary-sinusoidal connections, myocardial ischemia, necrosis, fibrosis, and systemic desaturation may occur. Areas of coronary stenosis and/or interruption of the coronary system may complicate this abnormality. No associated noncardiac conditions exist.

Frequency:

In the US: CAF accounts for 0.2-0.4% of congenital cardiac anomalies. Approximately 50% of pediatric coronary vasculature anomalies are CAFs.

Mortality/Morbidity:

Fistula-related complications are present in 11% of patients younger than 20 years and in 35% of patients older than 20 years. Larger fistulae progressively enlarge over time, and complications, such as congestive heart failure (CHF), myocardial infarction, arrhythmias, infectious endocarditis, aneurysm formation, rupture, and death, are more likely to arise in older patients. Spontaneous closure rarely has been reported.

Surgery-related complications: The mortality rate related to surgical repair of coronary arteriovenous fistulae typically ranges from 0-4%. Variations that may increase surgical risk include the presence of giant aneurysms and a right coronary artery-to-left ventricle fistula. Complications of surgery include myocardial ischemia and/or infarction (reported in 3% of patients) and CAF recurrence (4% of patients).

Race: No race predilection exists.

Sex: No sex predilection exists.

Age: CAF may present in patients at any age, but CAF usually is suspected early in childhood when a murmur is detected in an asymptomatic child. Older children with murmurs may present with symptoms of coronary insufficiency.

Imaging Studies:

Echocardiogram: Two-dimensional echocardiograms may reveal left atrial and left ventricular enlargement as a consequence of significant shunt flow or decreased regional or global dysfunction as a consequence of myocardial ischemia. The feeding coronary artery often appears enlarged, ectatic, and tortuous. High-volume flow may be detected by color-flow imaging at the origin or along the length of the vessel. Carefully seek the site of drainage; often, it is evident as a disturbed flow signal, most frequently within the right ventricle.

Cardiac catheterization remains the modality of choice for defining coronary artery patterns of structure and flow. Most frequently, intracardiac pressures are normal and shunt flow is modest.

Aortography (see cavf-1a, cavf-1b) or selective coronary arteriography (see cavf-3, cavf-4a, cavf-4b ) supplies the information required to manage the condition. In addition, therapeutic embolization using occlusive coils or devices may be performed via catheterization.

Spontaneous closure is rare but may occur in small fistulae. Small fistulous connections in the asymptomatic patient may be monitored. Most lesions enlarge progressively and warrant surgical repair, either by transcatheter or surgical techniques. Provide endocarditis prophylaxis in all patients.

Cardiac catheterization (transcatheter embolization) may be performed as intervention. Initial diagnostic catheterization should both define hemodynamic significance of the lesion and provide detailed angiographic assessment of the anatomy of the abnormality. Surgical options can be delineated by careful identification of the number of fistulous connections, nature of feeding vessel(s), and sites of drainage.

Transcatheter embolization is described as follows:

Indications: In view of the natural progression in larger fistulae to dilate over time, with progressively increasing risk of thrombosis, endocarditis, or rupture, the general advice is to close all but the small fistulous connections. In borderline situations, provide close echocardiographic or angiographic follow-up imaging to identify enlargement of feeding vessel in asymptomatic patients. Patients with large fistulae, multiple openings, or significantly aneurysmal dilatation may not be optimal candidates for transcatheter closure.

Technique: Transcatheter embolization techniques using coils, bags, or other devices can be performed on an outpatient basis at the time of diagnostic studies or later, and they obviate the need for cardiac surgical intervention. The transcatheter approach frequently is a fairly complicated intervention and requires an experienced operator and interventional specialist with expertise in both coronary arteriography and embolization techniques. Embolization often requires complicated catheter manipulation, as well as selection of various catheters and wires.

Surgical Care: Cardiac surgical intervention

is described as follows:

Indications: Indications for surgical intervention are the same as in embolization (see above). Some fistulae are unsuitable for the transcatheter approach and preferably are addressed surgically. These CAFs may include fistulae with multiple connections, circuitous routes, and acute angulations that make catheter positioning difficult or impossible.

Techniques: Surgical repair usually is approached via a median sternotomy and cardiopulmonary bypass. Identify the feeding vessel and delineate its course and site of insertion. Identify the site of presumed fistulous drainage prior to institution of the cardiopulmonary bypass. A typical procedure includes opening the chamber into which the fistula drains, identifying the fistula, and closing the suture. If the fistula enters the ventricle or if the feeding vessel is large, the coronary artery is opened, and the opening to the fistula is closed with a running suture. The arteriotomy is closed. Large aneurysms may require excision. Rarely, when the fistula is an end artery, it may be ligated with or without bypass.

Patients treated surgically and with transcatheter techniques

should receive maintenance doses of antiplatelet agents and,

perhaps, an anticoagulant regime for the first 6 months postoperatively,

until the operative surface has undergone endothelialization.

Patients remain at risk for development of endocarditis until the flow is stopped and should receive antibiotic prophylaxis for any dental, gastrointestinal tract, and urologic procedures.

Complications:

Complications of surgery include myocardial ischemia and/or infarction (reported in 3% of patients) and recurrence of the fistula (4% of patients).

Major complications associated with transcatheter embolization relate to manipulation of stabilizing catheters and wires in the coronary vasculature and may include coronary artery spasm, ventricular dysrhythmias, and perforation. Inappropriate positioning or proximal extension of occlusive coils or devices may result in obstruction of side branches and muscle loss. Intimal dissection of the coronary artery or thrombosis also may occur. However, morbidity and mortality rates generally are considered to be low.

Prognosis:

Further Outpatient Care:

Provide follow-up care after hospital discharge to check for evidence of ischemia or recurrence of fistulae. Individuals who have undergone coronary surgical interventions and, particularly, patients who have sustained cardiac muscle loss should have ongoing cardiac follow-up monitoring that may include stress studies and repeat angiography as needed.

Patients treated surgically and with transcatheter techniques should receive maintenance doses of antiplatelet agents and, perhaps, an anticoagulant regime for the first 6 months postoperatively, until the operative surface has undergone endothelialization.

Patients remain at risk for development of endocarditis until the flow is stopped and should receive antibiotic prophylaxis for any dental, gastrointestinal tract, and urologic procedures.

Complications:

Complications of surgery include myocardial ischemia and/or infarction (reported in 3% of patients) and recurrence of the fistula (4% of patients).

.Major complications associated with transcatheter embolization relate to manipulation of stabilizing catheters and wires in the coronary vasculature and may include coronary artery spasm, ventricular dysrhythmias, and perforation. Inappropriate positioning or proximal extension of occlusive coils or devices may result in obstruction of side branches and muscle loss. Intimal dissection of the coronary artery or thrombosis also may occur. However, morbidity and mortality rates generally are considered to be low.

Prognosis:

Recent results of both transcatheter and surgical approaches indicate a good prognosis. Approximately 4% of patients may require additional surgery for recurrence. Life expectancy is considered normal. However, risk of degenerative atherosclerotic disease may be higher if ectasia and dilatation of the coronary artery persist or progress. In young surgical patients, anticipate the involution of the dilated segment of the feeding vessel; this is not the case in adults.

Abstract

Coronary artery fistula is rare, but it is the most common congenital coronary artery anomaly with hemodynamic significance. It usually causes no symptoms in young patients but may be associated with symptoms and complications in older patients. Surgery has been the traditional treatment. In this report, a 7-year-old girl who had a coronary artery fistula from the left circumflex coronary artery to the right atrium was successfully treated by percutaneous transcatheter technique.

[Chin Med J (Taipei) 1997;59:194-8 Be-Tau Hwang M.D., Department of Pediatrics, Veterans General Hospital-Taipei, No. 201, Sec. 2, Shih-Pai Road, Taipei, Taiwan, R.O.C.

Introduction

Coronary artery fistula is a direct communication between a coronary artery and one of the cardiac chambers or vessels around the heart. Although the fistula is rare, it is the most common congenital coronary artery anomaly with hemodynamic significance. Analyses of large coronary angiographic series show the incidence of 0.1-0.2% . This particular anomaly usually causes no symptom in young patients but may present with symptoms and/or complications in older patients including congestive heart failure, myocardial ischemia, infective endocarditis, atrial fibrillation, pulmonary hypertension and rupture. Because of these complications, surgical closure has been advocated in most reported series . However, surgery usually requires a median sternotomy and cardiopulmonary bypass. The perioperative mortality rates range from 2 to 4 % . In this report, we describe the successful percutaneous transcatheter embolization of a coronary artery fistula by coils.

Case Report

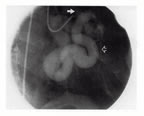

A 7-year-old girl was referred to this hospital because of a heart murmur. Otherwise she was symptom free, active and thriving. Physical examination revealed a grade 3/6 continuous murmur over the whole precordial area. Chest X-ray showed mild cardiomegaly. Electrocardiogram showed left atrial and ventricular hypertrophy. Two-dimensional echocardiograms disclosed a tortuous, dilated, tubular vessel from the aorta and around the heart. Color Doppler flow mappings demonstrated that the entrance of this abnormal vessel was located at the junction of the right atrium and ventricle. Cardiac catheterization revealed normal right and left ventricular pressures and a significant O2 step-up (74.4% to 88.5%) in the right atrium. The pulmonary to systemic flow ratio (Qp/Qs) was calculated as 2.5 by Fick's principle. Selective coronary angiograms (cavf-4a) disclosed a huge, tortuous, dilated coronary artery fistula from the left circumflex coronary artery with a single opening into the right atrium. A test inflation of a balloon of a 5 Fr Berman catheter showed that it produced complete occlusion without untoward clinical effects or electrocardiographic abnormalities. The coronary artery fistula was then occluded by using the Gianturco coils (Occluding Spring Coil, Cook, U.S.A.) through a 5F Judkins catheter. Three coils sized 10 mm in diameter and 12 cm long, 8 mm in diameter and 10 cm long, and 5 mm in diameter and 8 cm long were introduced sequentially. Transient myocardial ischemia with ST-T change was noted immediately after the procedure but spontaneously recovered one minute later. Postocclusion coronary angiograms (cavf-4b) demonstrated the complete occlusion without residual flow. The previous murmur vanished immediately. The follow-up Doppler echocardiography demonstrated a tiny residual flow into the right atrium 24 hours later. The prophylactic antibiotic, oxacillin, was given 30 minutes before the procedure and then administrated intravenously every 6 hours. However, high fever developed two days later. Blood culture was negative. One week after coil embolization, a pericardial effusion was found by echocardiography. The amount of effusion increased gradually in spite of aspirin administration, and so pericardial tapping was done on the 14th day after coil embolization. A total of 60 ml serosanguinous fluid was drained out and the fluid study revealed WBC 257/cumm, RBC 45,320/cumm, protein 4,400 mg/dl, and sugar 88 mg/dl. No bacteria was isolated from the fluid. The amount of pericardial effusion decreased gradually in the following days and was completely resolved two months after pericardial tapping. Follow-up study four months after coil embolization revealed that the patient is asymptomatic without cardiac murmur. The echocardiographic study showed minimal residual flow without pericardial effusion.

Discussion

Most coronary artery fistulas are believed to arise from the incomplete obliteration of primary myocardial sinusoids . This developmental arrest results in retained continuity between the mature coronary artery and cardiac vein or chamber . Although these fistulas are rare, they may gradually enlarge and become the most common congenital coronary artery anomalies with hemodynamic significance . Diagnostic methods include physical examination, electrocardiography, chest X-ray, echocardiography and angiocardiography. Liberthson et al. found that 91% of patients with these fistulas younger than 20 years were asymptomatic compared to 37% of patients older than 20 years. The symptoms or complications included congestive heart failure, myocardial ischemia, infective endocarditis, atrial fibrillation, pulmonary hypertension and rupture . Myocardial ischemia results from coronary steal, with the fistula acting as a low resistance pathway . Spontaneous closure of a fistula is very uncommon. On the basis of these data, most authors have recommended surgical closure of these fistulas during childhood even in the absence of symptoms . However, surgery requires a median sternotomy and usually cardiopulmonary bypass. The perioperative mortality rates ranged from 2 to 4 % in the literature.

Therapeutic transcatheter embolization of abnormal thoracic vessels was first reported in 1974 . In 1983, Reidy et al. reported the first case of transcatheter embolization of a coronary artery fistula. Since then, several reports had demonstrated the feasibility of transcatheter closure of coronary artery fistulas . Coils, detachable balloons, umbrellas and polyvinyl foam had been used for successful occlusion of these fistulas. The choice among these devices is somewhat arbitrary. Coils cost less than other devices and can be delivered through a smaller catheter . It is imperative that the feeding artery is occluded distal to all normal branches to the myocardium . The risks associated with transcatheter embolization of coronary artery fistulas include coronary artery disruption, pulmonary or systemic embolization, pericardial effusion , myocardial ischemia or infarction . In this case, transient myocardial ischemia occurred because the catheter induced left anterior descending coronary artery spasm during manipulation. The ischemia recovered spontaneously one minute later. Otherwise, aseptic pericardial effusion developed one week after coil embolization. The mechanism of pericardial effusion following transcatheter embolization of coronary artery fistula is unknown. It may be associated with increased hydrostatic pressure of pericardial vessels, pericardial inflammation or be similar to the postpericardiotomy syndrome after open heart surgery . After pericardial tap and anti-inflammatory agents with aspirin, the effusion disappeared gradually. Although there was a small residual flow by echocardiography in the reported case, the flow murmur could not be appreciated.

On the basis of our results and those previously reported , we believe that percutaneous transcatheter embolization is a safe and effective treatment for coronary artery fistulas. When a coronary artery fistula with hemodynamic significance is diagnosed, transcatheter embolization should be considered as a replacement to surgery.

2.

Cyanotic Congenital Heart

Disease features bluish discoloration

of the skin and lips as opposed to the normal pink appearance.

The cyanosis is due to the shunting of systemic venous blood

to the arterial circulation causing arterial blood desaturation

of oxygen. The size of the shunt determines the degree of desaturation.

In adults the most common causes of cyanotic congenital heart

disease are tetralogy of Fallot and Eisenmenger's syndrome.

a) Tetralogy of Fallot ( figure 23d )

b) Ebstein's Anomaly ( figure 23e )

c) Transposition of the Great Arteries ( figure 23h )

d ) Eisenmenger's syndrome ( figure 23j )Brickner,M.E. and others,Congenital Heart Disease in Adults,N.Engl.J.Med.,Vol.342.N4,2000,pp.334-342